I've been thinking lately about some of the compositional pitfalls that are specific to writing vocal music. I see student composers fall victim to these all the time, and established professionals don't always do better! Let's explore...

1. STRESSING THE WRONG SYLLABLES

When strong syllables don't get placed on strong musical beats, it doesn't sound right. Tap the beat while you sing this, and see what I mean:

I hope it's obvious why this is bad - when you speak these words, you naturally lean on certain syllables (“STRESS the cor-RECT...”). But by putting the first (weak) part of “correct” on the strong beat 3, the natural stresses of the text and music are working against each other. The rhythm isn’t serving the text.

Here it is, fixed:

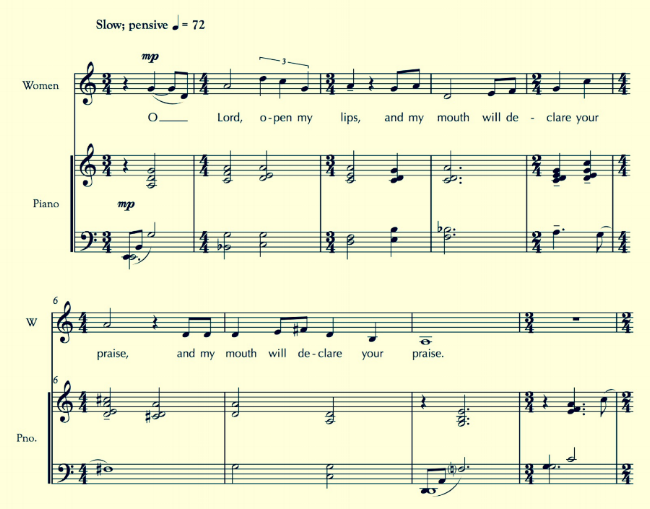

When the rhythm/phrasing is irregular, you can use mixed meter to keep strong syllables on strong beats. Here’s an excerpt from one of my liturgical settings - notice how every strong syllable is on a downbeat (or beat 3 of a 4/4 measure):

2. OVERWRITING

Three similar issues I see all the time:

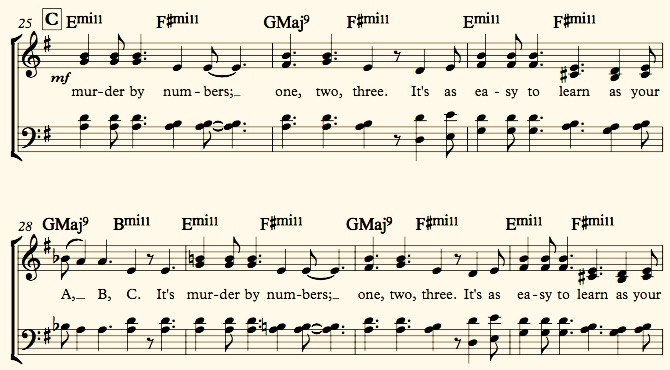

a. WAY, WAY, WAY TOO MUCH HOMOPHONY. So much contemporary choral music is dominated by chordal textures. “Chord-Chord-Chord” gets exhausting to listen to. I wish composers would utilize more counterpoint and independent lines. The great composers seemed to think this was a good idea, but it seems like many of today’s composers aren’t so interested in writing distinct horizontal gestures in each voice part.

b. CONSTANT DIVISI. There aren’t very many pieces that really need to be scored for 8 voices. When I hear a piece with a lot of divisi, I often feel like the composer is trying to use the “vertical busy-ness” to distract us from their lack of interesting musical ideas. Bach, Mozart, and countless others had no trouble writing nuanced, complex music in 4 voices. Why do so many contemporary choral composers and composition students think they need 6-8 parts all the time? It’s easy to throw down a bunch of thick, dense chords, but it’s much harder to deftly weave that many different parts into great music.

c. ALL THE PARTS SINGING ALL THE TIME. Even in music with fewer voices, if every section is singing the whole time, it’s going to get tiresome. Give each section a break. Writing rests is a compositional decision. Thinning out the texture will make your big moments more compelling by comparison.

3. SETTING UNMUSICAL POETRY

Every great poem is not a great poem to set to music. Here’s an example of an excellent poem that I would probably never use for a piece:

I like this poem a lot, but I don’t see a lot of room for music here. There are a few phrases that work (the last three lines are good, especially rising and gliding), but the others would be clunky to sing (When I was shown the charts and diagrams … where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room). These lines don’t feel inherently musical to me; they feel like prose.

In Jake Runestad’s recent interview with the International Choral Bulletin, he talked about setting text:

“There are so many engaging texts that have been written but not all lend themselves to being set to music. Many writings already contain all of the information (or too much information) one needs to experience their meaning. When searching for a text for vocal work, I seek words that are simple, direct, and communicate something about the human experience. These words must not be too flowery or too descriptive so that there is room for the music to add meaning of its own.”

“Simple and direct.” That’s the type of language that music brings to life most effectively. There’s a reason contemporary choral composers overuse Sara Teasdale. Look how much breathing room is in these lines. There is space for music to lift up the words: