We’ve all heard it. Someone is talking about an ensemble that has voices and instruments together, and they casually distinguish between the “singers” and the “musicians.” And by “musicians,” of course, they mean the instrumentalists. Now I don’t think most people who do this are implying anything malicious. I assume they actually know that singing is one way of being a musician, and that a singer’s voice is their instrument (the first instrument, in fact). But there’s a stereotype here: that singers somehow are not the real deal. That they aren’t as musically literate as their instrumentalist colleagues, and that they are perhaps less serious about becoming well-rounded musicians. I try to correct these generalizations when I hear them. Some of the very best musicians I know are singers, and there is, of course, no shortage of poor musicians who play an instrument.

But unfortunately, this stereotype doesn’t come from nowhere. In my experience teaching undergraduate composition, theory, and ear training, instrumentalists generally do better than singers. Why is this? I believe it’s because many music programs, especially ensemble offerings at the high school level, put more focus on teaching singers to become performers than on developing their overall musicianship.

Here in the midwest, at many high schools the most prestigious (and often the most select) vocal ensemble is a show choir. The nature of show choir necessitates that a large percentage of rehearsal time, thought, and energy be spent on non-musical elements: choreography, costuming, etc. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with these things, if this is the musical experience that teachers, parents and students value most highly, many schools will continue to produce Singer-Performers who are musically deficient. This is what I see happening.

What’s the solution? How do we help our singers build more meaningful musicianship? They can study theory, learn piano, and practice ear training. Musical theater repertoire and art songs are great for vocalists to develop their solo singing chops on serious literature. And, of course, having strong traditional concert choirs and select chamber choirs in our schools is extremely important - these ensembles go a long way toward developing musical IQ for singers.

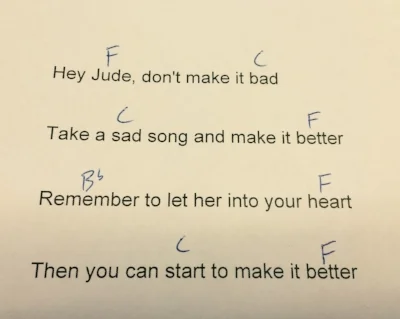

But I think another type of vocal ensemble does the best job of bridging the musicianship gap between instrumentalists and singers. It’s a genre that’s difficult to do well, but students love the challenge. Singers in this type of group develop killer ears and sight-read like monsters. It lets you program arrangements of popular songs and has the cool factor in spades. But no one is doing it.

More on this next time.