Okay, the title may be a little hyperbolic. Or maybe not. These four(ish) bars are near the end of Domine Jesu, in the Mozart Requiem. I’ve been wondering for awhile if I can think of four measures anywhere that are more satisfying.

Here’s why I think this ten second chunk of music is so great:

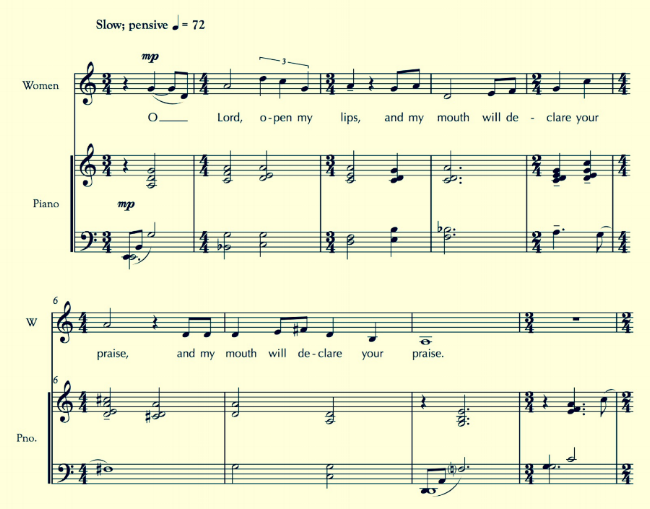

1. REALLY GOOD COUNTERPOINT. Look at the soprano and alto in the first three bars. When one sustains, the other moves. They fill in the gaps. It’s so smooth. Each of the four vocal lines moves distinctly from the other three. The initial entrances of the three upper parts layer down from the top like a Renaissance motet. Every voice has breathing room. It just feels good (which everyone knows is the best way to judge counterpoint, #analysis). Then, before you realize what’s happening, they’ve all joined together and fallen into the cadence. Slick.

2. THE DELAYED SUSPENSIONS. In the downbeat of the first full bar, the soprano is hanging on to the high G as the chord below shifts from E-flat major up to F major (more on this below). We expect the G to resolve down to F, a simple 9-8 suspension. Instead, it drops all the way down to C, the 5th of the F major chord, THEN jumps back up to the F we were originally expecting. By then the chord has changed, and now the soprano F is the 5th of a B-flat major 7th chord in first inversion.

In the next bar, it happens again (Sequence Alert!): the soprano F is tied over the bar, and for a split second - one eighth note - it’s the 9th over a new E-flat major chord. Then it quickly repeats the same melodic gesture: drops down by a 5th (again to the 5th of the chord), but this time when it leaps back up by a 4th, the bass note doesn’t change, so we finally get our 9-8 resolution - however briefly. This melodic sequence in the soprano is the hook that makes these first few bars memorable.

3. LET'S TALK ABOUT THAT F MAJOR CHORD. This piece is in G minor, where the 7th scale degree is normally raised to F-sharp (instead of F), since it’s the leading tone of the key. F-sharp also happens to be an essential pitch in a D major chord, which is the superimportant “V” in G minor. So we hear a lot of F-sharps throughout this movement. When the E-flat chord at the beginning of our excerpt shifts up to F major, it feels like Mozart has wiped the harmonic slate clean after all the previous F-sharps throughout the piece. We would label this chord “VII,” meaning a major triad that is built on the natural (lowered) 7th scale degree, as opposed to the leading tone. It’s not a particularly frequent chord in minor key-music of this era. Combine this with the soprano pitch G being tied over from the previous bar, and we essentially hear F(add9) at this important moment. Unexpected and beautiful.

4. GREAT COUNTERPOINT PART II: CHOIR v. ORCHESTRA. Just as the choral parts complement each other with just the right mix of long and short notes (largely half notes and quarters), the instruments are playing shorter eighths and sixteenths through this whole passage. Their quick, bubbling accompaniment contrasts the smooth choral texture above. The listener experiences multiple, distinct layers of counterpoint.

5. CONTRASTING WHAT CAME BEFORE. Here’s what happened before these four bars: the fugue (it starts at 2:00 in the video below) is full of quick, punchy gestures in all four voices. Very busy and active. Then at 2:46, the main motive gets passed back and forth between the sopranos and the other voices over a dramatic low D (dominant) pedal tone. This continues for four full bars, building up tension and momentum with the same busy melodic gestures. Then, finally, it opens up into these four measures. Suddenly, each voice is singing long, sustained notes in this beautiful and surprising harmonic progression. What a contrast.

To really feel how satisfying this short section of the music is, you have to hear it in context with the entire movement. The whole thing is less than 4 minutes, and our part starts at 3:03. Enjoy!